Chapter 1: Introduction and context

Background

This research was commissioned by Paul Hamlyn Foundation (PHF), under its Social Justice Programme. The Social Justice Programme has a particular focus on the integration of the most marginalised young people in the UK, and operates through grant funding and special initiatives. The Foundation’s objective in commissioning this research was to find out more about the lives of young undocumented migrants, to tackle a knowledge gap and to find out whether and how grant giving could benefit them. It was hoped that the results would reveal more about the areas of intervention that would most help the disadvantaged, and provide a robust and detailed understanding of the critical pathways in these young people’s lives. The first stage of the project was a scoping study carried out between April and July 2007. The scoping study highlighted the need to understand the complexity of the life processes, decisions and choices of young undocumented migrants, set within the context of their undocumented status. Informed by the scoping study, the main research study focused on the voices of young undocumented migrants, about which little is known, and explored their social and economic lives. More specifically, it examined their experiences of employment; social networks; community involvement; links and obligations with friends and family in their country of origin; how being undocumented impacts on their lives and their longer-term goals and aspirations. The project was carried out between March 2008 and June 2009, with the fieldwork taking place between August and December 2008. A requirement, and important part of the project, was that the process of doing the research should involve capacity building of the community researchers, the community organisation participants and partners, and the young undocumented migrants themselves. This involved networking and the development of new networks, the organisation of training and workshops, and activities signposting migrants to sources of help and support. These are described in Appendix 2.

Parameters of the study and definitions

The research set out to interview young undocumented migrants, so the starting point was to define the concepts of ‘young’ and ‘undocumented’. In terms of the age range, it was agreed after discussions with PHF and the project steering group, that the study would focus on people aged between 18 and 30. The study needed to define what it meant by ‘youth’ in this context. Young people grow up in varied economic and social circumstances, with different priorities and perspectives, and their gender influences their lives. Therefore, how young people shape their identity and negotiate their place in society – including their role as migrants – varies considerably, depending on a wide range of factors (Wyn and White 1997).

In order to understand the complexity of the situation of young undocumented migrants and shed light on their motivations and aspirations, the many competing, and sometimes contradictory, influences on them must be taken into account (Rose 1996; Hall 1992). According to Rattansi and Phoenix (2005), class, gender and ethnicity remain powerful in the formation of youth identities; this framework is mediated by the intersections of local and global factors. These propositions have particular significance for the study of young undocumented migrants, highlighting as they do a range of factors which will shape both the process and the experience of migration.

Migration represents, for many young undocumented migrants, a rite of passage in the transition to adulthood and to a new social role, but also a formative and transformative experience which shapes their present identity and their relationships with peers and society in general (Mai 2007). This research has explored, through the narratives of young people, the intersection of age and youth with the structuring influences of gender and ethnicity. It also looks at how these intersect with identity, decision making and aspirations, as well as their undocumented status; these variations are evident in the narratives. The concept of ‘undocumented’1 was defined in our study as people without authorised leave to be in the UK. Much of the literature stresses that different migratory circumstances, such as ‘undocumentedness’, should be seen as a process and strategy of migration, rather than a defined ‘end-state’ status (Ruhs and Anderson 2006). However, status is important because of the lack of rights associated with different statuses (Morris 2001, 2002; Kofman 2002).

The tension between the experience of ‘undocumentedness’ as a process and the official immigration categories forms an important part of our study, which focuses on the migrants’ own perceptions of what it is to be undocumented and how and why they might ‘migrate’ between the different forms of being undocumented or outside a particular status.

Inevitably, given the considerable complexity in agreeing definitive categories of immigration, residence and work statuses, the evidence on the numbers of undocumented migrants is contradictory. The biggest challenge is the lack of accurate data for this hidden population, and the data that do exist consist of estimates that do not disaggregate by country of origin, sex or age. The government has only recently adopted a standardised system of measurement (Home Office 2005), but this is problematic, not only because of the categories used, but also because it relies on data sources which are proxies for immigration status. Based on the 2001 Census, the Home Office estimates that the unauthorised (i.e. not necessarily the same as undocumented) population lay between 430,000 and 570,000 (Home Office 2005:5; see also Vollmer 2008). A recent report by the London School of Economics (Gordon et al. 2009) reviewed and updated the Home Office figure, adding in an estimate of UK-born children of irregular migrants. The LSE study gives a central estimate of 725,000 irregular migrants at the end of 2007, two-thirds of which are based in London.

Research context

This research examines the lives of young undocumented migrants, from their own perspectives. We will look at how they negotiate their way through the social and economic complexities of their undocumented status in a strange country, and find ways to survive and live their everyday lives. The research explores the processes by which these migrants are incorporated into the labour market, and the scope for action that the migrants themselves have within the structural constraints of global and local labour markets, along with government policies.

The research took place during a global economic downturn, as well as an era where migrants are encountering an increasingly managed immigration policy; a policy which has brought to an end virtually all avenues for regular migration for those from outside the European Union and for those without high or desirable skills. The economic downturn has affected the kind of immigrants that arrive and leave, as well as the livelihood strategies of those who stay (Papademitriou et al 2009; Zetter 2009; Martin 2009). More recently, with an increased focus on undocumented migrants, raids have been carried out on businesses that often employ undocumented migrants (or migrants who are semi-compliant and are therefore legally resident, but working in violation of some or all of the conditions of their immigration status). As the narratives in this study show, both the immigration policies and the economic climate have an impact on the lives of young undocumented migrants and the opportunities that they might have to enter the UK, work here and possibly regularise their status.

The ‘official discourse’ emphasises the negative and vulnerable conditions of an ‘illegal’ status, which firmer regulation might mitigate (see Boswell 2003). These imperatives provide part of the impetus for the increasingly stringent regulatory approach adopted by the UK Government (Home Office 2006, 2006a 2006b, 2007). However, as these recent government policy documents make clear, the case for increasing the regulation of migration appropriates and provokes the wider political discourse of ‘harm caused to the UK economy, society and individuals’ (Home Office 2007:10).

Migrants play a vital role in the labour market, with undocumented migrants usually located in the least regulated parts of the economy; these roles are characterised by low pay and other forms of exploitation (Ruhs and Anderson 2006; Spencer et al 2007). Undocumented migrants form a large reserve supply of low-paid and low-skilled labour to service professional and managerial workers. The global economic crisis and the resultant increase in levels of unemployment are already having an impact on the lives and experiences of the young people interviewed in this study, as there has been a decline in demand for the roles that many of them fill in the service sector, and a general worsening of their working conditions (see Chapter 4).

The government endeavours to regulate and manage migration, but there is no evidence that it has taken into account the (often undocumented) migrant labour necessary to sustain economic growth (Düvell and Jordan 2003; Castles and Miller 2003). Indeed, as May et al. (2006) emphasise, despite regulation, large-scale legal (i.e. regulated), low-wage immigration has still taken place. This has effectively driven down labour costs, with severe negative impacts on the working, health and social conditions of the migrant work force and their broader social cohesion (Hickman et al. 2008; Zetter et al. 2006). While some countries have used regularisation programmes to overcome the problems of undocumented migrants, the UK has limited experience of those problems. More recently, the Government declared a circumscribed amnesty for specific categories of asylum seekers whose cases had been pending for lengthy periods. The benefits of regularisation have been well documented (JCWI 2006). However, regularisation programmes have had extremely limited success since migrants believe that declaration of an ‘illegal status’ may be more likely to expedite removal than to guarantee the grant of leave to remain in the UK (Levinson 2005:30). Although there is currently a campaign for regularisation2, the economic crisis might affect the political expediency of such a strategy, and will also reduce the demand for the kinds of jobs that undocumented migrants tend to fill.

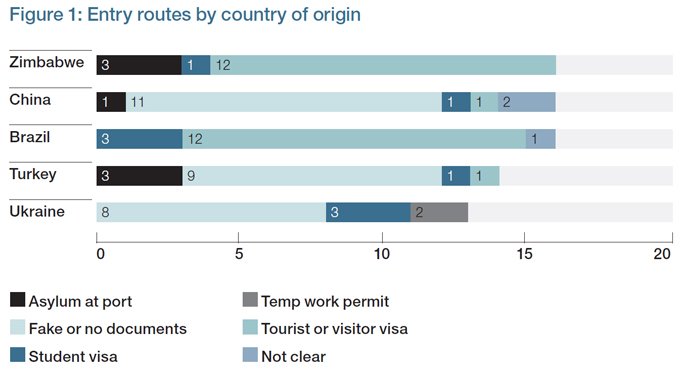

Fieldwork and methodology Our research was based on 75 in-depth interviews and testimonies with young people from China, Brazil, Turkey (Kurdish young people), Ukraine and Zimbabwe living in London, the North West and the West Midlands. Due to the lack of a sampling frame, interviewees were identified using non-probability methods. So, although the data provides in-depth insights into the experiences of young undocumented migrants from five country-of-origin groups living in England, generalisations cannot be made from the data to the whole population of young undocumented migrants (see Appendix 1 for a full discussion of the methodology and fieldwork). The countries of origin selected for inclusion in the study provided variation in terms of development; in the case of Zimbabwe, a country with former colonial links to the UK, and in Turkey, migration from a Kurdish minority suffering discrimination. There are also long and varying histories of migration to the UK. People from Turkey, Zimbabwe and China have long histories of migration to the UK and therefore have established community networks, while migration from Brazil and Ukraine is more recent and there are fewer community networks which might help to shape migrants’ experiences. The five countries of origin that we researched allowed for an exploration of different initial migration routes and strategies. These included student and work permit overstayers, the use of fake documents, those who had been through the asylum system and people who had paid smugglers to enter the UK clandestinely, as Figure 1 shows.

Although Figure 1 categorises the ways in which people actually entered the UK, many migrants used fake documents, acquired by smugglers or agents. Others travelled using fake documents and claimed asylum once they reached the border. In addition to those who claimed asylum at the border, 12 other young undocumented migrants – two Chinese, six Kurds and four Zimbabweans – have claimed asylum once in the UK, while a minority of others did not claim asylum because they feared rejection and deportation, so they preferred to remain outside of the asylum system. The migration processes and routes were often complex, involving multiple factors and, for some, a great deal of expense. Chinese young people almost always used the ‘snakeheads’ to organise their journeys, as summed up by the following quote:

In China, if you want to go to the UK, you pay a snakehead a certain amount of money. As long as the snakehead gets you in the UK, you pay them that agreed amount. How you get to the UK was the job of the snakehead. Whether you travel by plane or by ship is up to them. You must follow their arrangements. You can’t choose what to travel. They tell you what to travel. And that is it.

– Guo Ming, 30, M, Chinese3

The inclusion of very recent and less recent migrants allowed for a better understanding of how experiences are shaped and choices are made by young people over time. Around half the sample (33 out of 75) had been in the UK for three years or less, while 42 of them had been in the UK for four years or more. Young undocumented migrants from China were most likely to be more recent migrants, while those from Zimbabwe and Turkey tended to have been in the UK for longer.

Researchers fluent in the one or more of the languages of each of the five countries of origin were recruited to the project. The topic guide was translated and interviews were carried out in community languages, which were then translated and transcribed into English. Access to interviewees was through a number of organisations and faith groups, as well as snowballing from our initial contacts. Building relations of trust and interviewer verification by potential gatekeepers was crucial to the success of the project, and was a difficult and demanding process. Trust was built up by the researchers who were carrying out the interviews in first languages, and through contacts made by the research team during the scoping study and the main study. The researchers with linguistic skills were the first point of contact for the interviewees, and their skills were crucial to the success of the project.

Research ethics

Given the sensitivity of the research and the vulnerability of young undocumented migrants, ethical considerations and safeguards were paramount. The research was conducted following The British Sociological Association and Refugee Studies Centre ethical guidelines. The five researchers who carried out the interviews were all experienced in working with sensitive research topics and vulnerable groups. Even so, particular attention was paid to ensuring their awareness of ethical considerations and standards of confidentiality and anonymity were absolute. Regular debriefings were carried out during the fieldwork to ensure that these standards were maintained. All participants were interviewed after informed consent, although to protect their identities we did not require written consent. Participants were made aware that they could withdraw at any time, or request that parts of their narratives should not be recorded. Both withdrawal requests and omissions occurred. The researchers carrying out the interviews chose the pseudonyms used in this research; only they know the names and identities of the respondents. The recordings of the interviews and testimonies will be retained for 12 months, in case verification is needed, and will then be destroyed.

Profile of the sample

Of the 75 in-depth interviews/testimonies carried out, there were 16 each with young undocumented migrants from Brazil, China and Zimbabwe, 14 with Kurdish migrants from Turkey and 13 with Ukrainians. In the final sample, 44 interviews were carried out in London, 14 in the North West and 17 in the West Midlands. Forty interviewees were men and 35 were women. Twelve interviewees had children in the UK – six men and six women – and three women were pregnant at the time of the interview. Four people had children elsewhere and one had children in both the UK and Brazil. In terms of age, 34 interviewees were aged between 18 and 24 and 41 were aged 25 and over. While we had set an age range of up to 30, two of the Zimbabwean interviewees were 31 at the time of the interview. The diversity of the sample gives us the opportunity to explore intersections in the data by age, sex, region, and country of origin (see Appendix 3 for anonymised information about interviewees).

Outline and structure of the report

In addition to the introduction, the report contains six chapters. Chapter 2 examines the intersections of youth, migration, and of being undocumented. More specifically it explores the circumstances and motives for migration, as well as the extent to which the UK was a chosen destination, what was known about the UK before migration, the extent to which being young was an incentive for migration and a reason for being undocumented. Chapter 3 examines what it means, in reality, to be young and undocumented in the UK, and focuses on the everyday lives of young people, including accommodation and access to health and justice. Chapter 4 focuses on employment and livelihoods, particularly the working lives of young undocumented migrants, the impact of being undocumented on employment, the ways people find work without documents or valid documents and survival strategies during periods of unemployment. The chapter also examines people’s spending and obligations to pay back debts or send remittances, and the ways in which this impacts on their lives, employment strategies and choices. Chapter 5 considers the social and community lives of young undocumented migrants, including friendships, relationships, how people spend their time, as well as their engagement with organisations and groups. This chapter highlights the impact of English language proficiency on young people’s social and community lives and networks. Chapter 6 explores the aspirations and coping strategies of young undocumented migrants and their reflections on the experience of a young undocumented migrant in the UK. This chapter also explores the things young people do in order to escape the pressure and insecurity of their status, whether they make plans for their future and how they have adjusted and coped with changing life circumstances. Chapter 7 is the conclusion, which highlights the main findings of the research. The report also contains three appendices: Appendix 1 is the methodology, Appendix 2 documents the project’s capacity building activities and Appendix 3 is a list of interviewees, detailing their main attributes and their employment both in the UK and before migration.

Footnotes

- 1 For a discussion of the concept, including status definitions and categories, see the report of the scoping study www.staff.city.ac.uk/yum/documents/ Final_Report_YUM_Scoping_ Study.pdf

- 2 See www. strangersintocitizens.org.uk

- 3 All quotes will be followed by the age, sex and country of origin of the interviewee